Programação nutricional do desenvolvimento físico e do crescimento ósseo da prole por dieta materna hiperlipídica

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Resumo

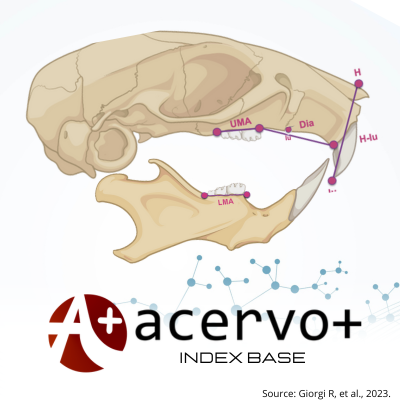

Objetivo: Investigar a influência do consumo materno prolongado de dieta hiperlipídica (DH), modelo animal para o padrão alimentar ocidental humano, combinado à obesidade pré-concepcional no desenvolvimento e crescimento da prole. Métodos: ratas Wistar foram submetidas à DH (52% de energia proveniente de gordura - principalmente de banha de porco) ou dieta controle (12% de energia proveniente de gordura) dos 37 dias de vida até o final da lactação. As mães do grupo DH apresentavam obesidade ao acasalamento. Após o desmame, todos os filhotes consumiram dieta padrão de laboratório. O crescimento somático, a maturação física, as avaliações neurocomportamentais, o desempenho locomotor e as medidas cefalométricas lineares da mandíbula (anteroposterior e comprimentos alveolares) e do crânio (diastema e comprimentos alveolares) foram avaliados em ambos os grupos de proles. Resultados: As proles do grupo DH demonstraram latência prolongada no reflexo de geotaxia negativa, erupção incisiva mandibular tardia e reduções notáveis no crescimento somático e em todas as medidas cefalométricas lineares quando comparadas ao grupo controle. Conclusão: A exposição materna prolongada à HD e a obesidade preconcepcional resultaram em atraso do desenvolvimento físico e do crescimento ósseo da prole.

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.details##

Copyright © | Todos os direitos reservados.

A revista detém os direitos autorais exclusivos de publicação deste artigo nos termos da lei 9610/98.

Reprodução parcial

É livre o uso de partes do texto, figuras e questionário do artigo, sendo obrigatória a citação dos autores e revista.

Reprodução total

É expressamente proibida, devendo ser autorizada pela revista.

Referências

2. BARKER M, et al. Translating developmental origins: Improving the health of women and their children using a sustainable approach to behaviour change. Healthc., 2017; 5(1): 17.

3. BERNARDIS LL and PATTERSON BD. Correlation between “Lee index” and carcass fat content in weanling and adult female rats with hypothalamic lesions. J. Endocrinol., 1968; 40(4): 527–528.

4. BERNICK S and PATEK PQ. Postnatal Development of the Rat Mandible. J. Dent. Res., 1969; 48(6): 1258–1263.

5. BOWERS K, et al. A prospective study of prepregnancy dietary fat intake and risk of gestational diabetes, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2012; 95(2): 446–453.

6. BUCKELS EJ, et al. The Impact of Maternal High-Fat Diet on Bone Microarchitecture in Offspring. Front. Nutr., 2021; 8: 1–8.

7. CADENA-BURBANO EV, et al. A maternal high-fat/high-caloric diet delays reflex ontogeny during lactation but enhances locomotor performance during late adolescence in rats. Nutr. Neurosci., 2019; 22(2): 98–109.

8. CERF ME. High fat programming and cardiovascular disease. Med., 2018; 54(5): 86.

9. CHEN J, ET AL. Inhibition of fetal bone development through epigenetic down‐regulation of HoxA10 in obese rats fed high‐fat diet. FASEB J., 2012; 26: 1131–1141.

10. CHEN JR, et al. Maternal obesity impairs skeletal development in adult offspring J. Endocrinol., 2018; 239(1): 33–47.

11. ESSELSTYN JA, et al. Evolutionary novelty in a rat with no molars. Biol. Lett., 2012; 8: 990–993.

12. FESTING MFW. On determining sample size in experiments involving laboratory animals. Lab. Anim., 2018; 52(4): 341–350.

13. GIRIKO CÁ, et al. Delayed physical and neurobehavioral development and increased aggressive and depression-like behaviors in the rat offspring of dams fed a high-fat diet. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci., 2013; 31: 731–739.

14. GRØFTE T, et al. Hepatic amino nitrogen conversion and organ N-contents in hypothyroidism, with thyroxine replacement, and in hyperthyroid rats. J. Hepatol., 1997; 26(2): 409–416.

15. HINTZE KJ, et al. Modeling the western diet for preclinical investigations. Adv. Nutr., 2019; (3): 263–271.

16. JENSEN KH, et al. Nutrients, diet, and other factors in prenatal life and bone health in young adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Nutrients, 2020; 12(9): 1–19.

17. KARALIS F, et al. Resveratrol ameliorates hypoxia/ischemia-induced behavioral deficits and brain injury in the neonatal rat brain. Brain Res., 2011; 1425: 98–110.

18. KIM HJ, et al. Three-dimensional growth pattern of the rat mandible revealed by periodic live micro-computed tomography. Arch. Oral Biol., 2018; 87: 94–101.

19. KUSHWAHA P, et al. Maternal high-fat diet induces long-lasting defects in bone structure in rat offspring through enhanced osteoclastogenesis. Calcif. Tissue Int., 2021; 108: 680–692.

20. LIANG C, et al. Gestational high saturated fat diet alters C57BL/6 mouse perinatal skeletal formation,. Birth Defects Res. Part B - Dev. Reprod. Toxicol., 2009; 86: 362–369.

21. MENDES-DA-SILVA C, et al. Maternal high-fat diet during pregnancy or lactation changes the somatic and neurological development of the offspring. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr., 2014; 72(2): 136–144.

22. ODIGIE AE, et al. Comparative non-metric and morphometric analyses of rats at residential halls of the University of Benin campus, Nigeria. J. Infect. Public Health., 2018; 11(3): 412–417.

23. OLIVEIRA TR dos P, et al. Differential effects of maternal high-fat/high-caloric or isocaloric diet on offspring’s skeletal muscle phenotype. Life Sci., 2018; 215: 136–144.

24. PARK S, et al. Gestational diabetes is associated with high energy and saturated fat intakes and with low plasma visfatin and adiponectin levels independent of prepregnancy BMI. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 2013; 67: 196–201.

25. POPKIN BM and NG SW. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev., 2022; 23(1): e13366.

26. REYNOLDS KA, et al. Adverse effects of obesity and/or high-fat diet on oocyte quality and metabolism are not reversible with resumption of regular diet in mice. Reprod. Fertil. Dev., 2015; 27: 716–724.

27. RUHELA RK, et al. Medhi, Negative geotaxis: An early age behavioral hallmark to VPA rat model of autism. Ann. Neurosci., 2019; 26(1): 25–31.

28. SANTILLÁN ME, et al. Developmental and neurobehavioral effects of perinatal exposure to diets with different ω-6:ω-3 ratios in mice. Nutrition, 2010; 26(4): 423–431.

29. SUTTON EF. Developmental programming: State-of-the-science and future directions-Summary from a Pennington Biomedical symposium. Obesity, 2016; 24: 1018–1026.

30. TELLECHEA ML, et al. The Association between High Fat Diet around Gestation and Metabolic Syndrome-related Phenotypes in Rats: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep., 2017; 7: 5086.

31. TOPPER LA, et al. Exposure of neonatal rats to alcohol has differential effects on neuroinflammation and neuronal survival in the cerebellum and hippocampus. J Neuroinflammation, 2015; 12(1): 160.

32. WALSH RN and CUMMINS RA. The open-field test: A critical review. Psychol. Bull., 1976; 83(3): 482–504.

33. ZHENG J, et al. Maternal nutrition and the developmental origins of osteoporosis in offspring: Potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Exp. Biol. Med., 2018; 243(10): 836–842.